|

|

|

|

|

748SPS Tech |

|

|

|

The Background

|

|

|

|

As this is written I can hardly believe there was so much to come from

a standard 748 Desmoquattro. For those who do not get the full Ducati range in their country a brief explanation is in order. There were three models in 1999, all using the same basic running gear and bodywork, the

differences as they say are in the details.

The Biposto, 748cc two seats (well almost!), pillion pegs and a steel rear subframe to hold up any porky

passengers. The engine uses 33mm inlet valves and very docile cams (both items the same as a 916/ST4, this good for just over 85hp and an 11800 rpm redline. The Biposto, 748cc two seats (well almost!), pillion pegs and a steel rear subframe to hold up any porky

passengers. The engine uses 33mm inlet valves and very docile cams (both items the same as a 916/ST4, this good for just over 85hp and an 11800 rpm redline.

The 748 Monoposto; irritatingly sometimes referred

to as a 748 Mono (IMHO a Mono is a motorcycle with one piston and one Barrel; see SuperMono tech for details!) sometimes comes with an Ohlins shock; otherwise it has the same engine as the BiP.

The third, the 1996 to 1999 748 SPS is a homologation special for World Supersport and

arguably the best, most fun motorcycle in the Ducati range. The motor has higher, and longer, lift cams, very slightly more compression, and an Intermediate exhaust system (ie 45mm down pipes and a

45/50mm crossover with 50mm open exhausts, the bike is delivered with open pipes and a chip to suit in the box). Most importantly the bike has had Pankl

titanium exhausts fitted, an earlier model, the 748SP had Pankl Steel rods. An Ohlins provides the rear suspension. A gorgeous aluminium rear subframe with a single seat is also fitted.

|

|

|

|

The effect of World Supersport regulations

|

|

|

|

If you look in to the Throttle bodies on a 748 you will find that it

has a 50mm butterfly, like all current Desmo quattro's but the down wind side has a 44m diameter 33mm long parallel sided flow restrictor, all 748's come with them.

The 1998 and 1999 models have a machined internal finish; the earlier ones, and those on BiPs have cast finish but the measurements are the same. This is an airflow restrictor, the equivalent is the 36.5mm diameter 27mm long restrictions in all current four cylinder 600's. No one remembers who thought up the balance of restrictors between twins and singles, initially it was 44m for twins and 36mm for fours, although it is rumoured it was someone called Bordi. The sizes were changed two years ago when Ducati announced a titanium rodded Supersport bike, their answer to the breaking rods plaguing the 13000 rpm race bikes; the extra half millimeter tipped the balance in the fours favour and Ducati have struggled in the class ever since.

An important point here, the titanium rods are not a power boosting option; they might make you feel like a works rider, they may make your wallet feel reassuringly lighter but their whole point is to reduce reciprocating weight. This means that the engine can be revved higher for longer with out overloading the crankcases or the bearings, power can come from higher revs but you need to modify other parts for that. The reduction in weight also means the engine picks up revs quicker, but it is a lot cheaper to fit a lightweight flywheel!

|

|

|

|

Going racing

|

|

|

|

We entered a Production class in 1999, very different to the limitless

modifications we could carry out in 1998 on the Supermono. The rules for the British Sport Production championship are very similar to US or Australian Supersport, very much a pipe and shock class, we even

need to keep the standard airfilters! The rules allowed for careful assembly; gaskets can be changed, so we could play with piston to head clearances but only anything mentioned in the Workshop manual can be touched, cam wheel and cam modifications are specifically banned. Finally, the Eprom (or jetting) can be changed; but the standard rev limit had to remain, top finishers would be tested on a mobile dyno to ensure no-one was being too economical with the truth…..

In current '600' terms the 748 is a bit on the porky side, we never got ours lighter than

181kg and, within a 'no carbon fibre' rule book we were trying quite hard (minus tank, on the FIM scales; the R1 next in line was 5 kg lighter!). We had an engine designed to rev 500 rpm higher (which is why

it got the Ti Rods) but we were not allowed to go over 11800 rpm. The bike couldn't get any lighter, so we had to concentrate on the power, and we had to get it at lower revs than the standard setup. There

were very few limits to suspension unit modifications, so we could also make it go round corners. Not being too proud to ask it seemed the fastest way to get up the finishing order was to take some advice. Steve

Wynne of Sports Motorcycles, Arthur Davis of Ducati Dealer Team Australia and Duane Mitchell of Fuel Injected Motorcycles all came up with tips (Gentlemen; please take your bows now; thank you!).

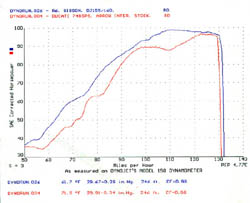

We decided on our strategy, we would be up

against opposition that weighed less and would have wider powerbands, both major advantages to them. See dyno chart 1 for an example (Geoff 002 is a standard 748SPS with open pipes and a chip

and Dynorun.026 is a dynojetted and piped Yamaha R6; both runs are 4th gear). This clearly shows the powerband advantage enjoyed by the fours, any gearchange and you are still in the

really good power zone, the 748 is clearly constrained by its rev limiter, just 500 more revs would mean we could gear it lower and stay in the good power during shifts, but as standard it was

also a bit lightweight. We needed to build the engine as carefully as possible, making as much power as we could, and at a lower rev level than standard if we could, without crossing the wording of the rules. We decided on our strategy, we would be up

against opposition that weighed less and would have wider powerbands, both major advantages to them. See dyno chart 1 for an example (Geoff 002 is a standard 748SPS with open pipes and a chip

and Dynorun.026 is a dynojetted and piped Yamaha R6; both runs are 4th gear). This clearly shows the powerband advantage enjoyed by the fours, any gearchange and you are still in the

really good power zone, the 748 is clearly constrained by its rev limiter, just 500 more revs would mean we could gear it lower and stay in the good power during shifts, but as standard it was

also a bit lightweight. We needed to build the engine as carefully as possible, making as much power as we could, and at a lower rev level than standard if we could, without crossing the wording of the rules.

Engine Tuning (or chassis tuning for that matter) is not about just bolting on new bits, that's what the fitters at your local dealer, or the guys at the Carbon Fibre emporium do. Tuning is about

deciding what the optimum settings are for a given collection of components to make them do what you want them to do; and then getting those components to the right settings so they can,

and do, deliver. This can include non-standard and modified components, sometimes this can mean losses in one area of performance but gains in the areas that particularly interest you.

The important thing is that, with a bit of effort and skill, parts and their settings can be optimised.

Ducati's are lovely; they are adjustable in ways that owners of other bikes can only dream of, the unfortunate side effect of this is that 'out of the crate' they are often not at the correct

standard settings. Ducati's are still a mainly hand built product, optimisation of the standard bits can make quite a difference. In choosing to compete in a pure production race series we were

about to have an advanced course in that.

Before we even ran the engine we took it apart and checked the sideplay at the crank and the

gearbox, not bad but we chose to change a few little things, we tightened up the crank and one of the gearbox shafts. We then put the engine back together, the next major item of interest being

the squish clearance (The distance between the periphery of the piston crown and the cylinder head). Normally one would modify the length of the barrel to get this dead accurate, the rules said

we couldn't do that so we cut our own, very thin, base gaskets to achieve the same end. We got the clearance as close as we dare (if you overdo it and the Piston touches the head or valves at

high RPM then things get very expensive very quickly), conversely if you do it right it is a very safe modification and the rewards are comparatively large.

The rulebook for the British Series said we could only do things that were in the Workshop Manual. Ducati, very obligingly, put the methodology for setting cam timing using offset keys in their

Manual so as far as we were concerned that was something legal; we would not need to modify the cam wheel or the cam to do it. Because of the weight of the bike we had come to the

conclusion that we need grunt out of corners more than we needed top end, we also need to give ourselves the widest powerband possible; reducing the overlap on the cams would give the bike more grunt.

We therefore decided to use an Eprom FIM had developed for the Australian Supersport championship, based on revised cam timing, similar to early Ducati Corsa's this setup was

intended to produce as much grunt as possible. Effectively shortening the barrel really threw the standard timing right out so we had some very large variations to contend with. The 'biggest

offset' key we have used on a standard engine is 4 degrees; the worst total variance between inlet cams 6 degrees; enough to make ones motor very rough running. This is a typical Ducati

manufacturing tolerance, this engine needed one 8 degree key; the inlet cam timing differential was over 8 degrees!

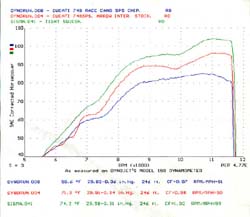

The attached dyno chart (No 2) shows three hp curves; the blue (Dyno run 008) is a standard

Ducati Biposto, with open pipes and an unidentified richer 'open pipe' Eprom. The red is Geoff Powells 748 sps with 50mm intermediate Termignoni's, this is after a service (not by us!) with the throttle

position sensor adjusted and the throttle bodies synchronised. The green is the best run we ever got out of our racer, if you look carefully you can see the peak actually takes place at lower revs;

the different cam timing shifts the whole curve to the left, just like the effect of a big bore job. The only differences between Geoff's engine and this one are the cam timing, the Eprom settings, the

squish and a very careful cam clearance and valve seat lap. I honestly cannot believe how effective the whole setup is; another 500 revs really would make a difference now. We rebuilt the top end of

the engine (lap the valve seats, set the clearances, ero everything else) every 200 miles to keep the power exactly where it was; with very regular oil changes we never needed to touch the bottom end. The attached dyno chart (No 2) shows three hp curves; the blue (Dyno run 008) is a standard

Ducati Biposto, with open pipes and an unidentified richer 'open pipe' Eprom. The red is Geoff Powells 748 sps with 50mm intermediate Termignoni's, this is after a service (not by us!) with the throttle

position sensor adjusted and the throttle bodies synchronised. The green is the best run we ever got out of our racer, if you look carefully you can see the peak actually takes place at lower revs;

the different cam timing shifts the whole curve to the left, just like the effect of a big bore job. The only differences between Geoff's engine and this one are the cam timing, the Eprom settings, the

squish and a very careful cam clearance and valve seat lap. I honestly cannot believe how effective the whole setup is; another 500 revs really would make a difference now. We rebuilt the top end of

the engine (lap the valve seats, set the clearances, ero everything else) every 200 miles to keep the power exactly where it was; with very regular oil changes we never needed to touch the bottom end.

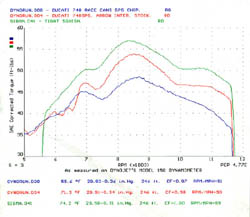

When you ride a motorcycle the thing you feel through the seat of your pants is the

torque (well alright, you also feel the bumps, especially on one of these….) Dyno chart 3 shows the comparative torque curves. The first model of the 748SPS had standard rods,

if you are not going to actually race (and hold it up at 11000 rpm plus for hours on end; therefore overstressing the rods) this makes a set of 748 sps cams and a careful engine build the real hot tip for the engine. Now if

you took it out to 853 as well you really would be laughing. When you ride a motorcycle the thing you feel through the seat of your pants is the

torque (well alright, you also feel the bumps, especially on one of these….) Dyno chart 3 shows the comparative torque curves. The first model of the 748SPS had standard rods,

if you are not going to actually race (and hold it up at 11000 rpm plus for hours on end; therefore overstressing the rods) this makes a set of 748 sps cams and a careful engine build the real hot tip for the engine. Now if

you took it out to 853 as well you really would be laughing.

|

|

|

|

Suspension & chassis

|

|

|

|

Now no one is going to argue that the standard 748 is a very well

setup motorcycle, Ducati did a brilliant job back in 1993; by current standards some thinking has moved on however, now the forks would run a little softer on springs, but with some more sophisticated damping.

We couldn't replace parts in the forks, well except springs, but we could modify things. So we did.

The standard hydraulic bump stop (inside the forks) was relocated to the circular file; the low speed damping was stiffened and the high speed shims modified to make up for the other two mods. Oil levels of between 130m and 105mm (95mm in extremis) were used, always Ohlins No5 fork oil.

The rear shock was revalved to 748 R spec; stiffer compression and rebound, higher gas pressure; the rear spring rate bumped right up. The effect of all these mod's was to hold the bike up under compression (ie as you push hard in corners), this meant that the chassis was held more stabley but the front perhaps a bit high. We chose to drop the front and raise the rear, the bike always ran with the forks in the more vertical setting. It took four race meetings before we got a consistent setup; one that allowed the rider to hammer the throttle in those wide arcs with a consistent feel from both front and rear, no tuck in, so front slide and decent drive from the rear.

Things to consider, if you change the rear sprocket by one tooth, say moving the rear

axle 8mm further back, the change of leverage, because of the variance in swingarm length on the shock is equal to 0.4kg on the spring, that is an awful lot. The feel of the bike changes dramatically with a

1mm difference in ride height; you will move at least 3mm in ride height with a one tooth change on the rear sprocket, more depending on where in the arc of the rear adjusters travel you are. You cannot race this

motorcycle without keeping an accurate measurement on the rear ride height, even if you do it will be a constant battle to keep track of the little changes that happen every time you move something.

The leverage on the shock with the change in length of the swingarm; the little differences in feel from the different angles in the Shock linkage when you correct for other changes, the need to keep the chainrun in the right place. This is a very sensitive motorcycle when you want to take it to its limit, but that limit is very high if you do…..

|

|

|

|

|

|