|

I sat down with a copy of Ian Falloons Ducati Story; if the V twins had been developed over

years since the Mono had been designed I had to find a way into the designers head, what had been done and why?

I was still in shock with the amount of money invested in the bike sitting in my garage, as a racer! I could not afford to make mistakes. The decision had been made to compete at Daytona, Fast Canadian Johnathan 'Corndog' Cornwell, a friend from the Superbike paddock had agreed to ride the bike in the Supermono race.

I would try and update the engine and the chassis to 1998 levels of performance. Johnathan is an

Ohlins technician, Carl Fogarty's actually, and agreed to come up with some ideas to bring the suspension up to speed. On the engine I did not want to reinvent the wheel, all I wanted to do was make the Ducati make

as much power as my old Air-cooled 686cc Yamaha, about 72hp on a good day. All I had ever heard, and Eraldo Ferracci confirmed, was that a good Ducati would be making around 65 to 68bhp. Given that an engine is just

a glorified air-pump and that the Yamaha was shifting the same amount of air at 8250 (its redline!) as the Ducati would shift at 10,000rpm. With water-cooling, a downdraft head and Desmo valve gear 72 hp couldn't be

that difficult could it?

I wrote down the details of every cam in the book, I worked out the duration's and the lobe centres, Some were quoted at different checking clearances just to throw me off the scent, I

added the valve sizes and the throttle body diameters, a pattern was coming out. Bigger valves as the capacity increased, long duration (very long duration!) cams for the sportier models,

indeed there were only 4 different cams, used in different ways, at different timings with different valve sizes, depending on the engine. I sat down and worked out the base calculations for my

old Yamaha engine, I had always believed in the smallest possible ports, in the idea that a jet of air from a smaller port would ultimately fill a cylinder better than a big hole and a slow draught was not new. I wrote down the details of every cam in the book, I worked out the duration's and the lobe centres, Some were quoted at different checking clearances just to throw me off the scent, I

added the valve sizes and the throttle body diameters, a pattern was coming out. Bigger valves as the capacity increased, long duration (very long duration!) cams for the sportier models,

indeed there were only 4 different cams, used in different ways, at different timings with different valve sizes, depending on the engine. I sat down and worked out the base calculations for my

old Yamaha engine, I had always believed in the smallest possible ports, in the idea that a jet of air from a smaller port would ultimately fill a cylinder better than a big hole and a slow draught was not new.

Friends got me drawings of the Ducati standard 50mm Throttle

bodies and the bigger racing 54mm and 60mm versions, the calculations clearly showed the logic, by the time the V Twin had 36mm valves and big cams it was being restricted by its injection

system. We had got a five horsepower boost out of the Yamaha five years previously with a set of bigger carburettors, the similarity of gas speeds and intake areas showed the the 'mono

needed more air. The 60mm bodies were just an attempt to completely lose the airflow restriction of the Butterfly mechanism, the 54mm would be big enough for just about anything we would

be able to achieve in the rest of the engine.

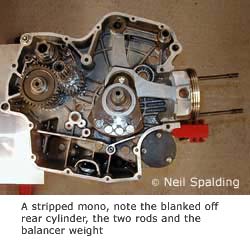

We were looking at the engine prior to reassembly when Bruce

Maus came round to see 'what one of those funny four strokes looked like'. Bruce had recently invested in becoming the 'SuPerTech' agent for Europe. SuPerTech is a surface treatment, best used when the parts are new that polishes the surfaces

so finely that very little running in is required. Three areas of the engine were of particular interest, the gears (all of them!) with their selectors, the cams and rockers and the piston and its

rings, the treatment gives a mirror finish and it certainly looks spectacular when the motor is apart.

The treatment proved successful, not only because the motor is so quick (it was fastest bike in all its

Euro SuperMono outings and in 1999, a year later, it was fastest Supermono in the hands of its new owner at Daytona with a 152 mph speed trap figure), but also because all the treated parts took

a major hammering and still came back for more. As evidence of this we carried out comparative compression tests on several bikes at Assen and the Sigma Ducati was well ahead with an excellent

leak down of a mere 5%, not bad for a 102mm piston! The treatment proved successful, not only because the motor is so quick (it was fastest bike in all its

Euro SuperMono outings and in 1999, a year later, it was fastest Supermono in the hands of its new owner at Daytona with a 152 mph speed trap figure), but also because all the treated parts took

a major hammering and still came back for more. As evidence of this we carried out comparative compression tests on several bikes at Assen and the Sigma Ducati was well ahead with an excellent

leak down of a mere 5%, not bad for a 102mm piston!

The target gas speed at peak horsepower was 350ft per sec, if we could get that and get the

'mono to make power at 10,000rpm I believed we would be making the Yamaha target. Alistair Wager bolted the engine together to factory spec, the throttle body was modified and an adjustable EPROM was fitted.

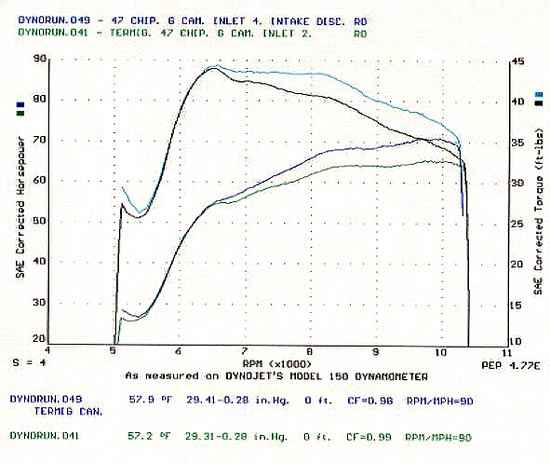

The first trip to the dyno was stunning, 70 bop and a nice flat torque curve, dyno chart 005

shows the outcome. I sat down and thought of all the 65bhp stories and had to pinch myself, 70 bloody hp on the first run. Next week we were back, different cam timing and more ideas, 65

bop. What had changed? We went through the possibilities, cam-timing back to standard, water temperature changed, air conveyors detached; AIR CONVEYORS DETACHED, that was it!

"The only difference between these curves is the air conveyors.

Dyno Run 49 is the state the engine was in for Daytona."

Removing the air conveyors, a piece everyone else was wiri ng tight (to keep the air in!) let the engine make 5 bhp more on the dyno. I sat down for a

long time to think. What was my target? It was useable power; power a rider could use everywhere, especially off corners at the start of straights, would the mono

make more power at higher speeds? Some research was needed on the likely power boost at speed. The best I could see from several books and articles (Sport Rider, July 1995 particularly) showed a best of 3% at

150 mph from airflow alone. By my calculations I decided I would prefer a 5 bhp increase off the 60mph corners and keep it at speed rather than struggle to make 2.1 hp at the end of the straight. ng tight (to keep the air in!) let the engine make 5 bhp more on the dyno. I sat down for a

long time to think. What was my target? It was useable power; power a rider could use everywhere, especially off corners at the start of straights, would the mono

make more power at higher speeds? Some research was needed on the likely power boost at speed. The best I could see from several books and articles (Sport Rider, July 1995 particularly) showed a best of 3% at

150 mph from airflow alone. By my calculations I decided I would prefer a 5 bhp increase off the 60mph corners and keep it at speed rather than struggle to make 2.1 hp at the end of the straight.

John decided to build a new rear damper. Everything moves on in the world, including the design of Ohlin's

shocks, and the shock on the mono had been designed back in 1992. A bit like engines, there would be some things that did not measure easily on a dyno but would

increase sensitivity and rider feel, we would have the lot. In keeping with good practice he also built a spare shim stack to return the bike to its original setting should we need it.

Neil Spalding

|